Many people hold a romanticised imagination of fieldworkers. They assume that fieldworkers can effortlessly “blend in like natives,” enjoy extraordinary folk experiences, and cultivate a sharp observation. This kind of imagination largely comes from ethnographic writing—texts shaped by meticulously woven theories, vivid portrayals of “natives,” and Márquez-like storylines. They feel a little magical, almost like science fiction. Bronisław Malinowski, one of the founding figures of modern anthropology, established a classic research model that includes long-term fieldwork, participant observation, language learning and understanding the world “from the native’s point of view.” This model attracted generations of scholars striving to write an ethnography as remarkable as Argonauts of the Western Pacific. However, after Malinowski’s death, his wife published his private diary from the Trobriand Islands, and people suddenly realised that the seemingly romantic life of fieldwork was nothing more than an illusion crafted within the ivory tower. A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term laid bare the hidden emotional landscape of this “model fieldworker”—depression, frustration, loneliness, and discomfort—forcing the anthropological community to confront, for the first time, the emotions and struggles that lie behind fieldwork. To be honest, I too once wrapped myself in that romanticism and plunged head-first into the world of fieldwork. Even after gaining years of experience and visiting one Indigenous community after another, I would still, from time to time, find myself trapped in that helpless situation, like the Chinese idiom says, “I’ve eaten bitter lotus root but can’t complain”—suffering silently with no outlet. If you were to open my field diary, you might expect pages filled with flashes of insight and cultural revelations—but no. What I recorded most often was my frustration over not being able to find a toilet in the forest. Blood and sweat in the field: The helplessness of female researchers I still remember my first arrival at a Batek village in Kelantan, when a sudden stomach ache hit me. To my surprise, all the brick houses were only half-completed products of modern civilisation: toilets had pits but no clean water source. In other words, villagers still had to go to the river to relieve themselves. Each family also had their own customary “invisible toilet” located along different parts of the river so that their waste would not meet. Perhaps out of urban modesty, I have only ever managed to relieve myself once in such open woodland. Most of the time, I would be on the verge of breaking down, trying my best to hold it until I returned to the foothill. Take the Jah Hut community as an example: I once followed villagers deep into the mountains to study their male initiation circumcision ceremony. When the urge to use the toilet struck, the boys were about to start their procession, visiting ancestral grave sites scattered across the area. The nearest household toilet was a 30-minute drive away. If I left to relieve myself, I would miss the heart of the ceremony. So, I followed a friend’s advice and performed a high-difficulty […]

2星期前

Ever since more locals learned that I’m researching the indigenous peoples of the Malay Peninsula, my inbox has occasionally popped up with unexpected invitations—to give talks, appear on shows, be in films, write books and so on. Because of a busy schedule and limited energy, I accept what I can; requests I can’t reply to or can’t commit to, I simply decline. But recently one email made a strong impression—and it came from someone in China. She told me she’s working on an American podcast called Spooked, whose host invites different guests each episode to tell their personal supernatural experiences. The woman emphasized that she was writing to me because she read my column, had been deeply struck by the indigenous worldview and was convinced I must have encountered similar eerie events during my research; she therefore invited me to be a guest on a new episode. Reading that, I couldn’t help but smile. Although I ultimately couldn’t make it, if I were to tally up my field experiences I might well be able to write an indigenous version of Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio. As a “secularized” city dweller, I once thought ghosts and spirits were merely products of human imagination. After all, things you haven’t seen with your own eyes are hard to believe. Once I even traveled to Si Puntum’s grave in Pasir Salak, Perak during the ghost month asking him to visit my dreams and explain why he assassinated the British Resident J.W.W. Birch in 1875. The idea came from oral histories among indigenous people that presented a version of events very different from the national history textbooks. At the time I dreamed nothing, but a few years later, while helping a local TV station to film a folklore program and coming into contact with many indigenous shamans and healing rituals, I unintentionally “switched on” a sensitive side of mine. Since then, supernatural presences have become an invisible companion I cannot ignore during fieldwork. Why are there so many ghosts here—from hitchhiking spirits to tea-cake-making grandmas? Take my fieldwork at Endau-Rompin National Park in Johor as an example: the scariest encounter was with a “hitchhiking ghost.” It always appears on the same stretch of road—whenever I drove past it, the car’s red seat-belt warning light would suddenly flash, telling me “the front passenger seatbelt is unfastened.” I was the only person in the car. So who, exactly, was sitting beside me? Another incident happened at the Urang Huluk’s forest clinic. That traditional healing space opens for four days and three nights at a time, so when choosing a place to sleep I deliberately picked the “nicest spot” that allowed the clearest view of the ritual. To my surprise, that day everyone praised me for being “so brave.” At first their compliments puzzled me, but after the third night I seemed to understand: on the first night I felt something beside me pulsing so that the wooden plank against my back shook. But when I opened […]

3月前

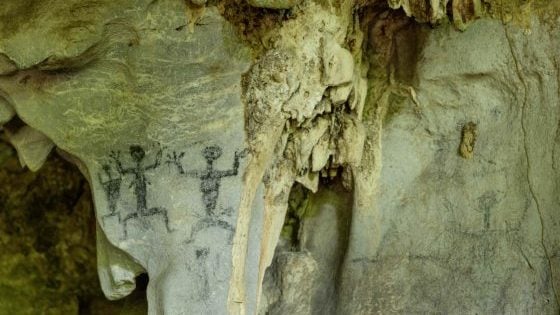

I have often pointed out that many of the so-called “tribal names” of the Orang Asli were creations invented largely for the convenience of British colonial administrators to classify and govern them. When these colonial officers could not effectively communicate with the children of the forest, they turned to external naming (exonyms). As a result, some of these names carry ambiguity or even negative connotations until today. Take the Orang Asli in Pahang as an example. Both the Semelai and Temoq tribes share oral histories of common ancestry, yet anthropologist Rosemary Gianno noted that the name “Temoq” was actually given by the Semelai, possibly derived from the Malay word tembok, which carries derogatory overtones such as “shabby” or “degenerate.” The Che Wong tribe’s name has multiple origin stories and was once referred to as “Siwang.” According to records, a British colonial officer, Ogilve, while serving in Temerloh, mistakenly thought a Malay forest ranger named Siwang was the name of a local tribe. Others have suggested that “Siwang” was in fact a reference to the Orang Asli religious ritual Sewang, misheard or misunderstood by the colonisers and thus recorded as a tribal name. As for the Temiar, who are found in the highlands of Pahang, Kelantan, and Perak, their name came from what the neighboring Semai called them. Anthropologist Geoffrey Benjamin proposed that “Temiar” may have derived either from the Austronesian root tambir or the Mon-Khmer word tbiar, both meaning “the edge.” From these cases, we see that although early Orang Asli societies did not have the concept of “race,” they already had a sense of “us” and “them.” Such distinctions were often expressed through mythological tales. One upstream Urang Huluk in Johor once told me: in the beginning, the world had only a single well, and all humans drank from it. Later, someone wished for kopi O (black coffee), and the water turned into coffee. Those who drank it became the darker-skinned Orang Asli and Indians. Someone else wished for teh tarik, and thus the Malays were born. Finally, when someone desired teh C (milk tea with evaporated milk), the Chinese people came into being. Another Temiar elder in Kelantan told me: in ancient times, the Malay Peninsula was struck by a great flood that nearly wiped out all life. Only a brother and sister survived. Orphaned, they floated on a raft and eventually settled on Mount Yong Belar, at the Kelantan–Perak border. One day, the brother saw two lice mating on his sister’s head and suddenly grasped the mystery of reproduction. He then united with his sister, and from their offspring came the whites, the Orang Asli, the Malays, the Chinese, and the Indians. Of course, such stories are the realm of anthropology. Archaeologists, by contrast, do not talk about “races” but instead classify people by eras and material evidence. Into Kelantan’s Ancient Caves in Search of “Little Dancing Figures” My first encounter with the Temiar was in mid-August this year. They were the ninth Orang Asli group I […]

3月前

Whenever I meet new friends, they always ask me the same question: “How do you manage to find those Orang Asli villages?” And I always reply, “No idea.” It may sound absurd, but I’m hopeless in identifying direction. I often get lost even when driving in the city, let alone in remote mountains where GPS signals vanish into thin air. Every time I head to a new place, I’m filled with anxiety. I worry that if I go too far, I might never find my way back. But strangely, there’s always a mysterious voice in my head urging me to dive into new adventures. In June 2019, when news broke of 16 Bateq tribe members were found dead in Kelantan, the urge to uncover the truth firsthand grew stronger than ever. But passion and a sense of mission alone were far from enough. To find this Orang Asli village, I scoured the internet for the names of journalists who had reported the story. While covering parliament, I privately asked fellow reporters for leads. Eventually, persistence paid off—one TV journalist shared the route with me, and a Chinese newspaper reporter helped me get the village’s GPS coordinates from British anthropologist Ivan Tacey. With this precious map in hand, I still needed to contact the Bateq village head before setting out. So I tried every possible way to find organizations connected to the Bateq. That’s when I discovered Klima Action Malaysia, an environmental group that had previously raised funds for them and was about to organize a climate march. To get in touch with their president, Nadiah, I pitched a story idea hoping to use the coverage as an excuse to ask her for the village head’s contact. This preparation phase took nearly two months—and I still couldn’t reach the chief. But since we had already booked our accommodations, my team and I had no choice but to go. After six hours of driving, passing towns with Jawi signage, Siamese villages where people didn’t speak Malay, Bangladeshi worker quarters, and endless oil palm plantations, we finally arrived at an empty village. Panicked, I called Nadiah again for help. She answered with a tone like the end of the world: “The Bateq are hunters-gatherers. When they go into the forest to forage, they can be gone for a week—or even a month.” Trial 1: How to cross the home of the leech army Before meeting the Bateq, we didn’t really understand what “hunter-gatherer” meant. Driven by curiosity and patience, we finally met them after three days and got the village head’s consent to interview them. The first Bateq phrase we learned was “Cep Bah Hep” (Let’s go into the forest)—a phrase they say all the time. One day, after much persuading, three villagers finally agreed to take us into the forest to show us how they normally gather food. They said the trip would take about two hours. But surprise! We entered in broad daylight and didn’t return until nearly dusk—five hours later, […]

5月前

I often hear all kinds of mythical stories whenever I wander through the forest. Some warn humans to beware of demons and spirits, while others praise the protection of ancestral spirits and deities. However, in the world of the indigenous people, there is one figure that is both good and evil. It is believed to devour human souls while also being the guardian of forest. This controversial “creature” has many names. In North America, it is called Bigfoot or Sasquatch; in the Himalayas, it is known as the Yeti; and in Malaysia, one of its names is Mawas. Yes, it is the mysterious, unproven creature that frequently appears in world mythology—Bigfoot. Records about Mawas are scarce, with the earliest documents tracing back to the British colonial era. At that time, explorers heard stories from indigenous people about encounters with Mawas deep in the Peninsular Malaysia. These accounts often describe it as a creature standing six to 10 feet tall, covered in long black or reddish fur, resembling an ape, and possess supernatural abilities that allow it to move swiftly through the forest. But where has Mawas been sighted? According to a 2005 report, three workers reported seeing three Bigfoot-like creatures near the indigenous village of Mawai in Kota Tinggi, Johor. Later, massive human-like footprints were discovered nearby, with one measuring up to 45 centimetres long, causing a sensation both locally and internationally. The following year, the Johor state government even formed a forest expedition team to verify the existence of Mawas – Malaysia’s first official search for a mythical creature. Mawas enters children’s theatre Regardless of whether the Johor government ultimately found Mawas, I recently had my own “encounter” with one! But instead of being in the south, it was in Selangor. A few months ago, I was invited by Shaq Koyok, an indigenous artist from the Temuan tribe, to visit his village and witness this legendary Mawas. To my surprise, its appearance was adorable and amusing – completely different from what historical records describe. In reality, it was part of a cross-disciplinary art project called “Awas Mawas” (Beware of Bigfoot). The initiative was led by sculptor William Koong, visual artist Forest Wong, theatre director Ayam Fared, community art advocate Fairuz Sulaiman, and performing artist Malin Faisal, with support from Orang Orang Drum Theatre. Inspired by the Bread and Puppet Theatre in the United States, this artistic group spent three weeks in Temuan and Mah Meri villages, discussing myths and land issues with the locals. During this time, they encouraged children to create their own stories and characters, incorporating adult perspectives, and then worked together to craft giant puppets using eco-friendly materials like cardboard, dried leaves, and bamboo strips. Among these were Mawas, the Temuan ancestral spirit Moyang Lanjut, and the Mah Meri ancestral spirit Moyang Tok Naning. At the event’s finale, this “modern-day Mawas” acted as the narrator, leading the entire village in a cultural parade, while the children performed two different theatrical plays. These plays aimed to […]

9月前

更多Orang Asli